Back to Basics on Probiotics, Prebiotics, and Synbiotics

The research on gut health has rapidly increased over the last decade and as the ever-growing body of science expands, so do the conversations around it. There are some key words that are guaranteed to come up in every gut discussion, but what exactly do these terms mean? In this post, we go back to basics and dive into the definitions of probiotics, prebiotics, and synbiotics.

Let’s begin with a reminder of what the gut microbiota is.

GUT MICROBIOTA

Comprising of trillions of microorganisms, the gut microbiota inhabits our gastrointestinal tract and influences various aspects of our physiology. The bacteria in our gut microbiota play a key role in maintaining our health and are involved in many mechanisms including absorption of nutrients, vitamin synthesis and communication with major organs and systems.1-4

Fact checker: Are the microbiota and the microbiome the same?

The terms ‘microbiota’ and ‘microbiome’ are often used interchangeably, however, they do have their differences. The microbiota is the community of microbes which reside in the gut or specific community. The microbiome describes the entire habitat in an environment including the microbes, their genes and metabolites.

The composition of the gut microbiota is affected by a number of different factors – some we can’t change (non-modifiable factors) and some we can (modifiable factors). One of the biggest modifiable factors that influences our gut microbiota is diet, with some of the key players being probiotics and prebiotics.

WHAT IS A HEALTHY GUT MICROBIOTA?

There is no core “healthy” microbiota that is common to all individuals – in fact, our gut microbiota is as unique as our fingerprint. Nevertheless, there are three characteristics that are considered key: diversity, stability and resilience. Studies have shown that these characteristics are associated with healthy long-living people and the absence of gut microbiota-associated diseases.5-9

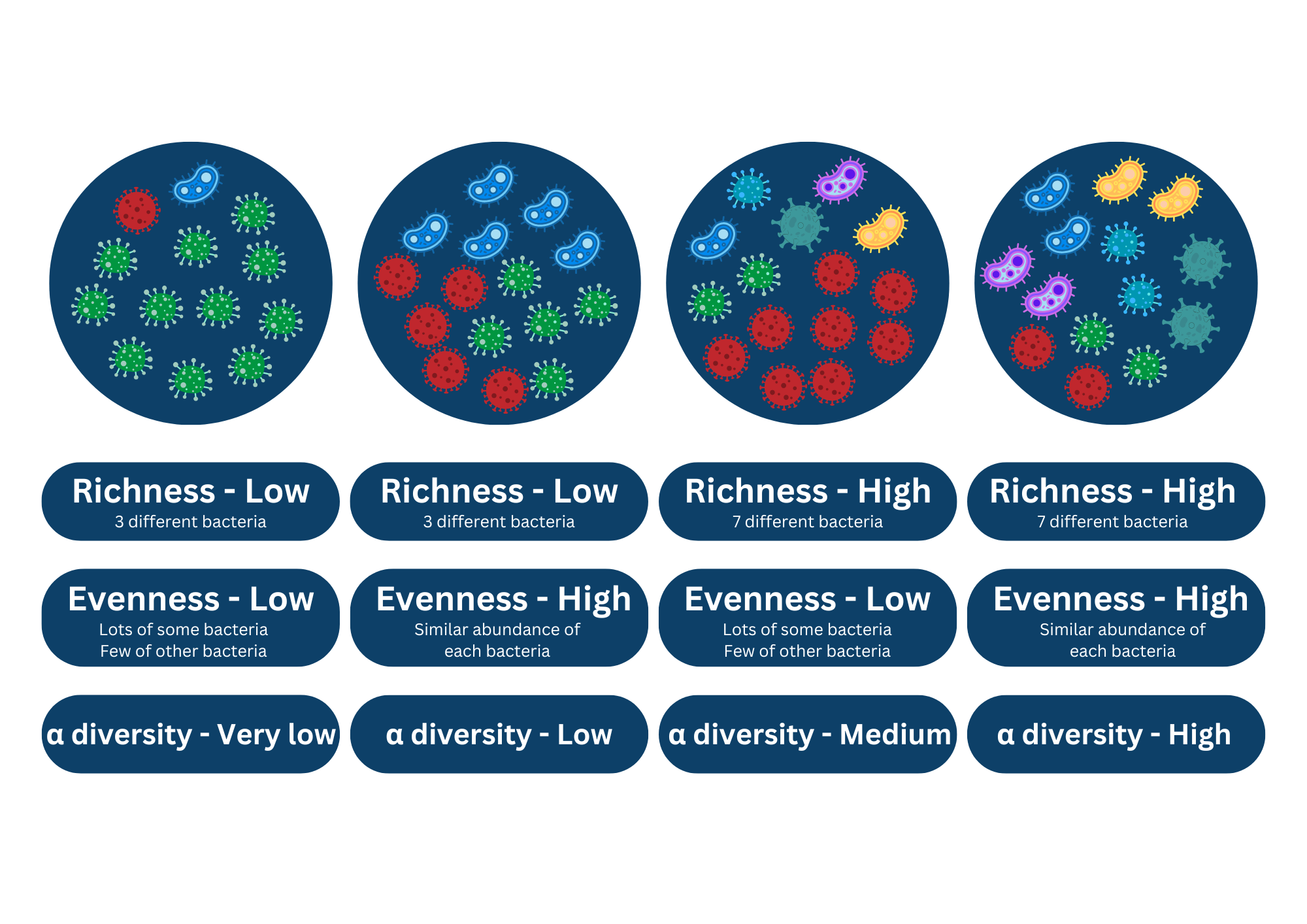

Diversity is a key characteristic but also an important measurement for a “healthy” gut microbiota, alongside richness and evenness. See below for their definitions.

Definition checker:

Microbial Richness: The number of different microbial species present in the gut.

Microbial Evenness: The relative abundance of different microbial species in the gut.

Microbial Diversity: The number of different microbial species present in the gut (richness) and their distribution/evenness.

Find out more in our Get To Know The Gut resource.

PROBIOTICS

A term that is often in the gut health limelight is probiotic, but what exactly is the official definition?

Probiotics are defined as “live microorganisms that, when administered in adequate amounts, confer a health benefit on the host”.10

Probiotics can lead to changes in the composition and function of our gut microbiota. For a probiotic to result in a health benefit, the live microorganisms consumed must survive the gastrointestinal tract and reach the large intestine alive.

It is essential that probiotics are classified and labelled correctly as health outcomes are strain-specific i.e., different probiotics strains have different effects. Put simply, not all probiotics are the same. For a probiotic to be labelled sufficiently, it must include the genus, species, and strain. For example, ‘Lacticaseibacillus’ (genus), ‘paracasei’ (species), ‘Shirota’ (strain).

It is crucial to know the exact strain that is present to check there is research in the health outcomes of interest for your patients.

Fact checker: Are probiotics and fermented foods the same?

No. Not all fermented foods are probiotics. This is because they do not meet the official probiotic definition due to the fact that fermented foods generally contain undefined microbial strains in varying amounts and their potential health benefits have not been demonstrated in well-controlled intervention studies. In addition, many fermented foods on the market are heat-treated, meaning that they do not have live microorganisms in the final product. Some examples of fermented foods that do not contain live microorganisms are bread, wine, and most beers.

PREBIOTICS

If you’ve heard of probiotics, you’ve probably heard of prebiotics. But how are they different?

Prebiotics are defined as “substrates that are selectively utilised by host microorganisms conferring a health benefit”.11

Prebiotics are selectively fermented by beneficial bacteria into short chain fatty acids (SCFAs) and can increase bacterial growth (e.g., ) leading to an increase in gut microbial richness (the number of different species present within the microbiota). This is one of the important indicators of a “healthy” gut microbiota. However, microbiota changes following prebiotic consumption are specific to the individual.12,13

The most widely studied prebiotics occur naturally in foods e.g., inulin, lactulose, galacto-oligosaccharides (GOS), and resistant starch.

Fact checker: Are all sources of dietary fibre a prebiotic?

No. All prebiotics are dietary fibres, but not all dietary fibres are prebiotics.

Examples of dietary sources of prebiotics include:

- Chicory

- Leeks

- Legumes

- Jerusalem artichoke

- Bananas

- Beans14

To date, there are no UK dietary recommendations for prebiotic consumption, however, the International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) recommends a daily intake of at least 5g of prebiotics per day.15

SYNBIOTICS

Lastly, that leaves us with the term synbiotic. Currently it’s not as widely used as probiotic or prebiotic but one to look out for as new research emerges. So, what is a synbiotic?

Synbiotics are defined as a “mixture comprising live microorganisms and substrate(s) selectively utilised by host microorganisms that confers a health benefit on the host”.16

Whilst this definition makes it temping to describe a synbiotic as a combination of a probiotic and a prebiotic, this is not quite accurate. To be considered a synbiotic each component on its own does not necessarily need to meet the criteria of probiotics or prebiotics. Therefore, the definition becomes a little bit more complex.

Studies exploring the effects of synbiotics on the gut microbiota show that they promote the growth of commensal bacteria (which exist to benefit the host without causing harm, supply essential nutrients and defend the host against opportunistic pathogens), such as Bacteroides.14, 16 This supports gut diversity, one of the key indicators of good gut health.

Note: ISAPP state that probiotics and prebiotics can only be classified as synbiotics if they have been tested together.16

Key takeaways

- The gut microbiota inhabits our gastrointestinal tract and influences various aspects of our physiology. The bacteria within our gut plays an important part in overall health and has many different roles within the body.

- There is no ‘one size fits all’ when it comes to the gut microbiota as everyone’s gut is as unique as a fingerprint. However, 3 important characteristics of a “healthy” gut are diversity, stability, and resilience.

- Probiotics, prebiotics, and synbiotics contribute to increased richness within the gut microbiota.

- Our dietary patterns as a whole contributes largely to our overall health, however, some people may benefit from taking a probiotic, prebiotic, or a synbiotic to help support specific health outcomes. Remember, different probiotic strains have different affects.

Keen to read more now? Download our free Diet Diversity guide.

References

- Thursby et al (2017) Biochem J, 474(11): 1823-26

- Carabotti et al (2015) Ann Gastroenterol, 28(2): 203

- Hadadi et al (2021) Curr Opin Endocr, 20, p.100285

- Cook et al (2022) Gut microbes, 14(1), p.2068365

- McBurney MI et al (2019) The Journal of Nutrition, 149(11), 1882–1895

- Deng F et al (2019) Ageing, 11(2), 289-290

- Lozupone C et al (2012) Nature, 489(7415), 220-30

- Mosca A et al (2016) Frontiers in Microbiology, 7, 455

- Rodríguez JM et al (2015) Microbial Ecology in Health and Disease, 26, 26050

- Hill et al (2014) Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 11(8): 506-514

- Gibson et al (2017) Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 14:491-502

- Ruberfroid et al (2010) Br J Nutr 104(S2):S1-63

- Davis et al (2011) PloS ONE 6(9) :e25200

- Slavin (2013) Nutrients 5(4) :1417-35

- ISAPP (2017) Prebiotics. Available at: https://isappscience.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/Prebiotics_Infographic_FINAL_rev0919.pdf (Accessed: 08 January 2024)