News

Our interview with Dr Majdi Osman

Dr Majdi Osman is a doctor and lecturer in medical microbiology and infectious disease. He is the Chief Medical Officer of OpenBiome, a non-profit stool bank that collaborates with clinicians, hospitals, and researchers to make faecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) safe and affordable for patients suffering from recurrent C. difficile infection. Additionally, Dr Osman is a Co-Principal Investigator on the first FMT trial in Africa, the THRIVE (Transfer of Healthy Gut Flora for Restoration of Intestinal Microbiota via Enema) study, at the University of Cape Town in South Africa. His research focuses on improving children's health through understanding the microbiome and reducing health disparities. In our interview with Dr Majdi Osman, we find out more about his career and research…

1. Can you share with us your career path, and what led to your interest in infectious diseases? Why did you decide to move into microbiome work, and in particular focus on faecal microbiota transplantation (FMT)?

I studied medicine in London and have always had an interest in global health and how we can improve access to new health services for areas of the world that don't have them. My family comes from Sudan originally and part of that interest was born out of experience from family members and friends who couldn't access many of the most basic things.

During my work in medicine, I was involved in various global health projects and then afterwards spent some time at the World Health Organization working on diarrheal diseases and malnutrition in children. It was eye opening for me how science can be used to influence policy and to develop new ways of treating conditions that remain burdensome and significant for health systems and for communities around the world.

Then I started my medical training in infectious diseases, came over to Boston to do a masters in public health and during that time met the founders of Open Biome. I was drawn in by the potential of this organization. There were about four of us on the team and then eventually we grew to a team of nearly 100 people. My first experience with FMT was actually back in the UK. There was a patient who’s C. diffiicile infection wasn't clearing after courses of antibiotic therapy. This patient, unfortunately, wasn't really going to be ideal candidate for a surgery. And so the consultant suggested consider fecal transplant. We found a donor, prepared the treatment and got the patient’s endoscopy arranged because in those days we couldn't freeze the sample. After the patient was treated, the next week they were up and they were healthy.

That event was a signal to me that FMT is something that could. firstly, be done in a much easier way and, secondly, be organised so that people aren't having to arrange it all themselves. That experience of FMT combined with the my public health experience of malnutrition and diarrhoea, has always suggested that perhaps there are ways the microbiome plays a significant role in those diseases as well. And we can potentially not just through FMT, but maybe through other interventions like food or probiotics, modify the microbiomes and these diseases.

2. You are the Chief Medical Officer of OpenBiome which is a non-profit organisation based in the U.S. Can you share with us the aim(s) of OpenBiome and what some of your main responsibilities are as the Chief Medical Officer?

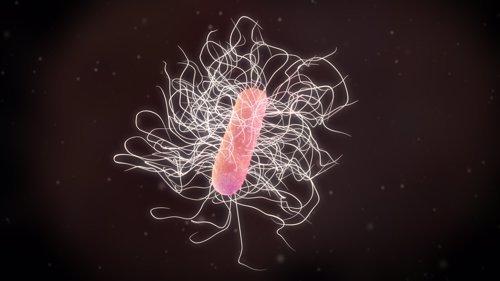

Open Biome is a non-profit based in Boston,US and we started because of 1 patient, a young man in his early 20s who had just come out of college, was looking forward to his career and had a gallbladder surgery - a very straightforward one to remove. Then he developed C. difficile infection shortly after, probably because of the antibiotic that was being used. C. difficile is a very nasty diarrheal disease that is responsible for maybe 30 to 40,000 deaths a year in the US. This young guy went through rounds of antibiotic therapy and still wasn't responding. He was having diarrhoea five, six times a day, wasn't able to get a job, facing all the common problems that many people who have C. difficile face.

At the time, he had to wait several months to get a FMT or faecal transplant and would have had to drive to one of the big cities like New York or San Francisco to get a treatment. Unfortunately, he decided to take matters into his own hands like many patients were doing and found a friend and had them provide a stool sample and basically did the FMT himself. Listening to this story, it was shocking that in America, one of the wealthiest countries in the world, patients were having to do this for treatment that was recommended at the time by the medical societies. So Open Biome really was founded to fix that problem. We thought initially this is going to be something that would be providing faecal transplants to hospitals just in the Boston area and then fast forward a few years later and we're working with over 1200 hospitals and have treated nearly 65,000 patients across the US. So our first mission is to enable safe access to FMT and our second mission is to support and catalyse research in the human gut microbiome.

3. For those who aren’t familiar with FMT, could you briefly explain what it is and how it can support patients with recurrent C. difficile infections?

Faecal microbiota transplant or FMT involves the transfer of gut bacteria from a healthy individual to the person with the disease. It's been described as far back as 380 AD by a Chinese physician called Jihong, who would leave a stool sample out to dry from a healthy individual and add water to it and provide it to patients when they came to him with diarrhea.

We've moved on obviously from that in terms of the delivery, but the principle has stayed pretty much the same and in the 1950s there was another person called Ben Eisenman from the US Navy who treated 5 patients using FMT delivered by colonoscopy and was able to treat these patients successfully for C. difficile. The other big milestone was in 2014. It was a randomized control trial that compared FMT to vancomycin for the treatments of C difficile. Vancomycin was the last line antibiotic therapy for C. difficile infection but they found FMT to be just as, or more, effective than vancomycin.

4. What is the process for donating stool samples and conducting FMT? How are risks associated with FMT minimised in the process?

The treatment itself is taking a sample from a healthy individual and transferring it to the person with a particular disease. But what makes it difficult is that the sample, just like a blood test or any kind of tissue donation, needs to be safely screened because you want to make sure that no diseases are going to be transferred or you're reducing the risk as much as possible. The first step is a clinical assessment, so we screen them for around 200 different conditions and risk factors, and these range from infectious disease risk factors like travel all the way through to non-infectious diseases, mental health conditions, diabetes, gastrointestinal conditions since there’s alot of research showing associations between the gut microbiome and many of these factors.

What we want to make sure as much as possible is that we aren't increasing the risk of an individual receiving an FMT having that disease. So the second step is a blood test assessing for infectious diseases. And the last step is a stool test where we assess for all the common viruses and bacteria that can cause gastrointestinal infections and we also screen for Sars-Cov-2 because it appears that it can be shared through stool. Overall the pass rate to become a donor is just below 3%.

Once the donor passes, we then collect samples. The donors undergo regular testing of the stool and blood as well in a clinical assessment.

And then when the sample is provided, we turn those samples into treatments. The treatments are prepared either into liquid formulation for colonoscopic delivery or via upper endoscopy. or capsules. The treatments are put in the freezer at -80⁰C and sent to the clinician when they are ready to treat a patient. It’s just like ordering any other drug basically.

We just published the paper on this and based on the outcome from randomized control trials, the clinical cure rate is around 80 to 90% which is really exciting for many patients who run out of treatment options.

5. You are also a Co-Principal Investigator in the THRIVE study, the first study to explore FMT for the treatment of malnutrition in children who are unresponsive to standard therapy. Could you share with us the aim(s) of this study and some of the current findings?

The THRIVE study is looking at the potential of the transfer of gut microbiota from healthy individuals to children with severe acute malnutrition that have failed nutritional therapy and antibiotics. We know that about a third of children with malnutrition don't respond adequately to nutritional interventions . Even when the interventions are being delivered optimally.

What's emerged in recent years is that the gut microbiome potentially plays a causal role in the recovery from malnutrition. By transferring gut microbiota from children with malnutrition to germ-free mice, those mice adopted a malnourished state despite being fed the same diet as mice with healthy gut microbiota. And importantly, when you are able to restore the gut microbiota of these mice that were transfused with malnourished microbiota, they are able to recover. That suggests that potentially, the combination not just of feeding but potentially addressing the microbiome as well may improve outcomes in malnutrition.

FMT is a treatment that is recommended for C difficile infection in Paediatrics by the medical societies here in the US and we were interested in seeing with our collaborators at the University of Cape Town whether FMT in the population of kids with malnutrition that have failed multiple rounds of feeding therapy could potentially improve outcomes there. This is a very small pilot study of 10 children receiving the treatment and 10 in the control group. We wanted to assess the feasibility, acceptability and gather some preliminary information on the safety as well. It's a condition that unfortunately still affects millions of children per year but potentially if we do see any promise with this, it's safe and efficacious later down the line, and could offer insight into developing new therapies. It may also offer an option for those children who are at the very last line of therapy and who have failed other interventions.

6. You have had quite a multicultural experience, growing up in UK and Sudan, and currently residing in Boston, USA. What are your favourite things about these places? Has this multicultural experience influenced your personal and professional growth in any way?

Firstly, I feel very lucky in so many ways to have been able to have these experiences, to live in different places, to have been able to learn from both life experience, some really great universities and work in some really exciting places doing things that are both interesting and hopefully will be impactful one day.

Living in these different contexts has highlighted that we still face a situation where much of your health is determined by where you're born. Having been fortunate to have lived in these different places. I hope to pull all of these different experiences together to hopefully contribute one day to health in Sudan as well, which is a country that suffers from high rates of malnutrition, diarrhoeal disease and other infections.

These are really complex problems and obviously are there inequalities in the outcomes for many of these diseases, but we might actually learn from each other as well. In many places around the world that don't necessarily have the wealth of Europe and the US, there are these amazing community health worker programs, for example, that perhaps we in the US and Europe are lacking.

I think these experiences feedback on each other and hopefully can help us all have better, healthier, happier lives. Not to mention the food as well. I think that's important. I've been lucky to live in places with lots of really good food!