News

The fate of probiotics through the gut

Very few studies are dedicated to elucidating the fate of probiotics directly in the human gastrointestinal tract. This information is crucial to the understanding of mechanisms and physiological effects of these type of microorganisms. In the light of such need, a recent publication by Takada and colleagues1 investigated the changes in the small intestine after a single intake of fermented dairy products in seven healthy men. The participants ingested a drink containing either Lactobacillus casei Shirota (L. casei Shirota; 10.9 ± 0.1 Log10 cells) or Bifidobacterium breve strain Yakult (BbrY; 10.8 ± 0.1 Log10 cells) or both. A marker, made from non-absorbable polyethylene glycol, was used as a reference for transit comparisons and estimation of cell’s viability.

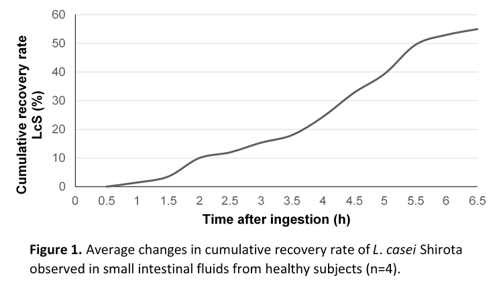

The study found that in many of these individuals, their small intestine fluids were temporarily dominated with more than 1 billion cells of the ingested microorganisms, representing over 90% of the ileal microbiota. The increase was observed to start after the first 2-hours of having consumed the fermented drink with an average peak at about 4 hours. In the majority of the subjects, L. casei Shirota was found to transit faster and in relatively higher abundance in the gastrointestinal tract when compared to BbrY.

The average number of recovered cells at the terminal ileum was 10.8 ± 0.2 log10 cells for both L. casei Shirota and BbrY, with an average recovery rate of 78 ± 39% and 104 ± 39% respectively. Furthermore, this rate had the same pattern as the non-absorbable marker indicating that the strains did not colonise the intestines.

The viability of the ingested strains was determined by culturing of ileal fluid content. This revealed different patterns among subjects. For L. casei Shirota, viability ranged between 10 to about 55% whilst for BbrY from less than 2% to above 60%. The trials did not find a negative correlation between bile acid concentration and the probiotic’s viability.

Overall, the findings show that L. casei Shirota does not colonise the intestine but does occupy it for a period of time. This, according to the researchers, is long enough to guarantee the interaction of the bacteria with immune, nerve and glia cells, a key aspect that allows a physiological effect. The study also demonstrated that both L. casei Shirota and BbrY cells are able to reach the intestine alive, a key characteristic for probiotics. When consumed, strains are exposed to gastric, bile and pancreatic juices. It is well known that to be considered a probiotic, the bacteria have to resist these drastic changes in the environment and keep being viable.

In addition, this study showed a clear distinction between individuals in aspects such as observed strain’s survival rate and subject’s bile acid concentration. Such differences confirm the assumption that the host may influence the physiological effects of probiotics.

References

1. Takada et al. (2020) Gut Microbes 11(6):1662-1676

25/08/2020